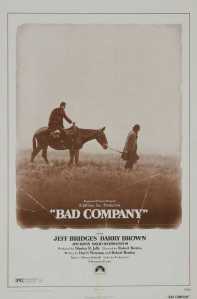

Bad Company

by Robert Horton

About a decade ago the early 1970s were officially enshrined as the last golden age of Hollywood, especially (probably not coincidentally) by the filmmakers and critics who came of age during that time. This view has some nostalgia attached to it, and at times it distracts people from appreciating some of the important work being done right here, right now.

About a decade ago the early 1970s were officially enshrined as the last golden age of Hollywood, especially (probably not coincidentally) by the filmmakers and critics who came of age during that time. This view has some nostalgia attached to it, and at times it distracts people from appreciating some of the important work being done right here, right now.

But an awful lot of good movies came out of that epoch, including smaller movies that — even at the time — were overlooked in the tide of Godfathers and Chinatowns. Here is an absolute gem: Bad Company, from 1972, the directing debut of Robert Benton. Written with Benton’s longtime writing partner and Bonnie and Clyde co-scribe, David Newman, Bad Company is the kind of Western that people were making at the time: revisionist, ironic, modern. Strangely enough, this particular revisionist Western is also full of its own beauty.

There’s not a lot of story. The time is the Civil War, and the hero is young Drew Dixon, an Ohio lad, played by Barry Brown. Hustled from home with his parents’ help (“When you get to a town,” mother advises, “you seek out the Methodist Church”), he is fleeing from conscription in the Union Army by heading west. (So many Westerns from this era were really about the Vietnam War, and draft evasion was a potent issue at the time.) Hoping to hook up with a wagon train in Missouri, Drew lands instead in the company — bad company it is, too — of a group of scalawags, “hand-picked for gumption.” They are led by the scruffy Jake Ramsey, played by Jeff Bridges.

This gang of self-styled outlaws heads west, and stumbles into one miserable situation after another. Most of the film is comically curved around the ineptitude of these supposedly bad hombres, but despite the humor Bad Company does conform to a particular vibe of the era; its de-romanticizing of the Old West is shot through with bracing shock tactics. For instance, a boy runs to an isolated farmhouse to steal a pie from the window sill; all is high spirits as the chickens scatter and he dashes towards safety. It’s plenty funny until, without having been prepared in any way for it, the top of his blond head comes bloodily apart, taken by the discharge from the farmer’s unseen shotgun.

There was a lot of that kind of thing in early ’70s cinema, dating from around the time of Bonnie and Clyde; not only were audiences not comforted and coddled, they were actively provoked. Yet the overall tone of Bad Company is not angry or self-righteous. What you’ll remember about this movie is the way its hard-bitten revisionism supports a genial, sympathetic appreciation of human beings. That, of course, is a hallmark of the subsequent directing work of Robert Benton, from Kramer vs. Kramer to the blissful Paul Newman vehicle Nobody’s Fool. As a neophyte director, Benton was remarkably poised; he captures the entire atmosphere of a frontier town, as well as a crucial change in fortune for Drew Dixon, in a single loooong traveling shot early in the film. The cinematography, by echt -’70s DP Gordon Willis, is muted and unfussy but somehow definitively modern throughout.

Benton also served notice of his talent with actors. Jeff Bridges, still very much at the beginning of his career (baby fat intact), is as unactorly and authentic as you could hope. Rotund David Huddleston contributes a pinpoint portrait of a dandy-ish bad guy, whose posse of henchmen (including redoubtable character men Ed Lauter and Geoffrey Lewis) is an unending source of embarrassment to him — there’s just a touch of Lex Luthor from the 1978 Superman there, a film Benton and Newman helped write. Evidently Huddleston’s performance is an impersonation of Joseph L. Mankiewicz, director of the Benton-Newman script There Was a Crooked Man. And John Savage made his film debut as one of Jake Rumsey’s crew.

But the person I always think of when I think of Bad Company is Barry Brown. He was a supremely likable and intelligent performer, and in this film he channels an upright James Stewart to Bridges’ junior John Wayne. Brown played one more leading role, in Peter Bogdanovich’s Daisy Miller (1974), another film that is overdue for re-evaluation; he was, superbly, a sad-eyed Winterbourne to Cybill Shepherd’s dippy Daisy. After that Brown pretty much dropped off the movie map, dying by his own hand in 1978, and for years his bio information in the Internet Movie Database has read, “Shot himself to death,” a blunt, slightly archaic sentence that might have come from Drew Dixon’s diary.

Drew’s gradual corruption — and, perhaps more importantly, his warming comradeship with Jake — leads to an abrupt ending that is just exactly right, in retrospect (compare it with the ending of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and work backwards, and you’ll see which film is more honest about its subject). From first to last, Bad Company is a classic.

Filed under: On Classics, On Directors | Tagged: Bad Company, Barry Brown, Jeff Bridges, Robert Benton |

Leave a comment